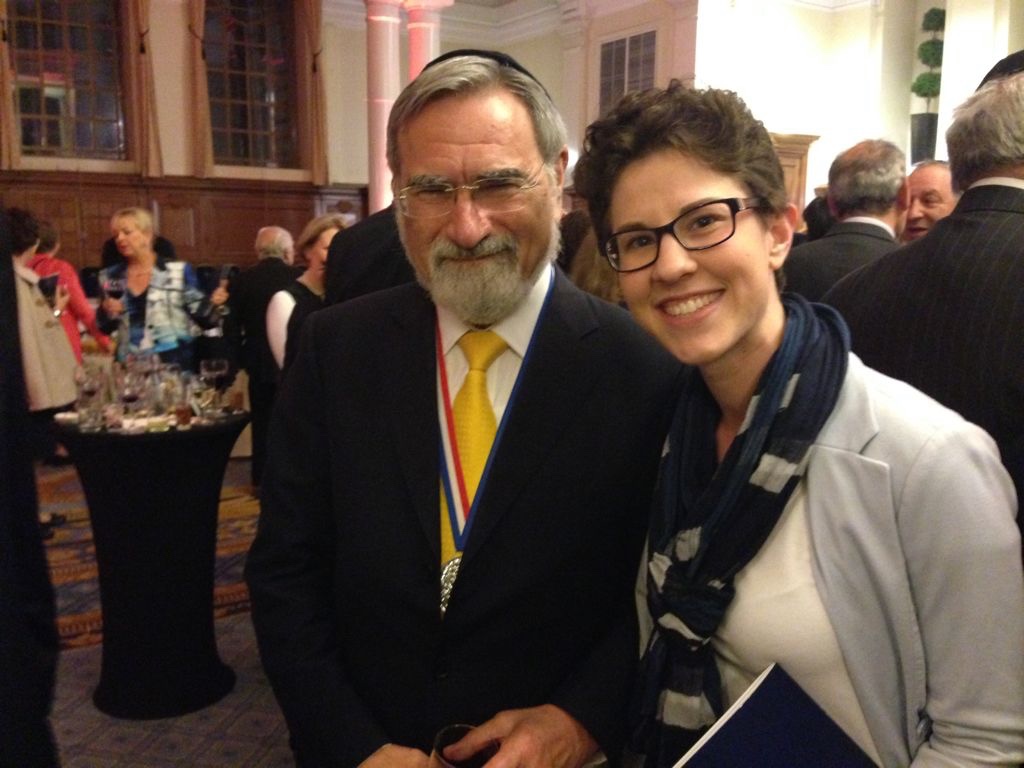

Recently I have been reflecting on a particular chapter in the last book Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks published just before his death. The book is titled Morality: Restoring the Common Good in Divided Times and the chapter that I have in mind is titled “Victimhood.”

Rabbi Sacks opens the chapter with a discussion of Yisrael Kristal, a Holocaust survivor who lived to be 113.

During the Holocaust, Yisrael’s wife and children were murdered. And, after years in ghettos and concentration camps, he weighed just 82 pounds.

We learn that Yisrael remained a religious Jew throughout his life. He married another survivor with whom he had children and they settled in Haifa and opened a business selling sweets and chocolates as he had done in Poland.

Rabbi Sacks goes on to compare Yisrael Kristal to Abraham insofar as Yisrael was able to integrate into his life completely the transformative idea: “To survive tragedy and a trauma, first build the future. Only then, remember the past.”

“There are real victims,” Rabbi Sacks affirms. “And they deserve our empathy, sympathy, and compassion. But there is a difference between being a victim and defining yourself as one. The first is about what happened to you. The second is about how you define who and what you are. The most powerful lesson I learned from these people I have come to know, people who are victims by any measure, is that, with colossal willpower, they refused to define themselves as such.”