Throughout Pope Francis’ pontificate, he has been emphasizing the value of encounter between the young and the old. One of my favourite quotations ever of his is this: “We, the elderly, can remind young ambitious people that a life without love is arid. We can say to young people who are afraid that anxiety about the future can be beaten. We can teach young people too in love with themselves that there is more joy in giving than in receiving. The words of grandparents have something special for young people. And they know it.”

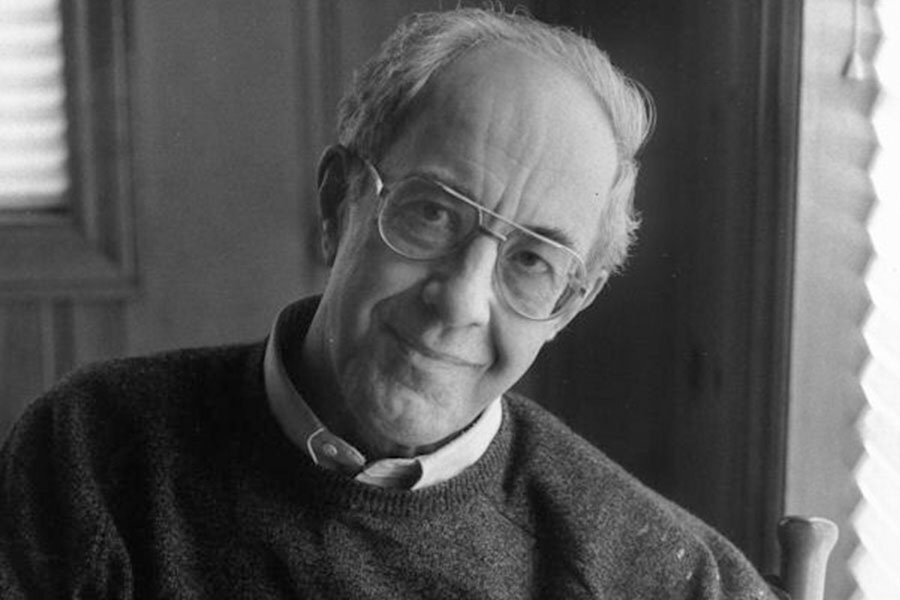

I think the reason I appreciate this quotation so much is because these are indeed the very things my grandfather taught me and, equally, the very things I most needed to learn from him.

My grandfather was deaf in his 80s and 90s, but his mind remained sharp until his death. I wrote to him A LOT and was the scribe at family dinners, usually transcribing the flow of the entire conversation for him.

One day, several years ago, I decided to ask my grandfather what he hoped I would do in my future, what he thought I would be.

The answer he gave me in this 1-minute clip is one of my most precious memories.

Indeed those words were special, and I knew so right away.