Here is a short piece I wrote a few ago on the value of and the possibility for intergenerational friendships.

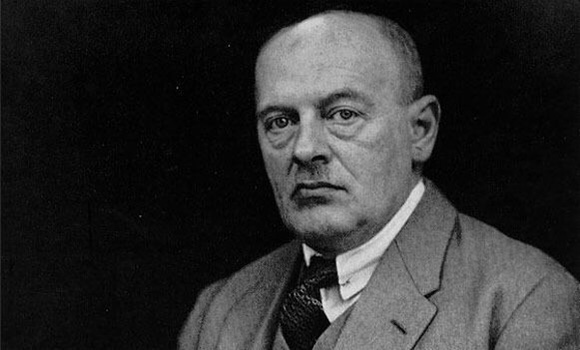

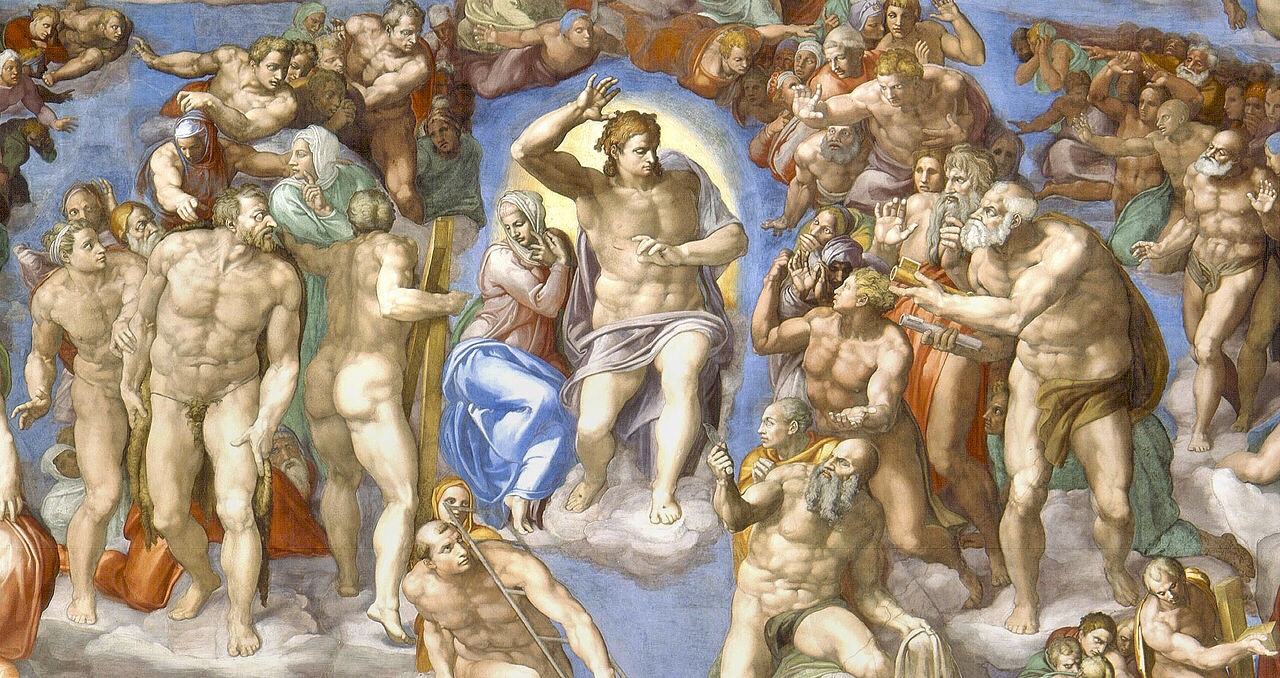

During the Year of the Family, Pope Francis devoted one of his Wednesday addresses to the elderly and another one to grandparents. He thinks that part of the culture of death is a poverty of intergenerational friendships: “How I would like a Church that challenges the throw-away culture with the overflowing joy of a new embrace between young and old!” What are the obstacles to such an embrace? In his Ethics, Aristotle observed that young people tend to seek pleasure in friendships and that the old tend to seek friends for utility, but that good, enduring friendships involve being friends for the other’s own sake. Given the distinct tendencies to which the old and young are prone, can they actually be friends?

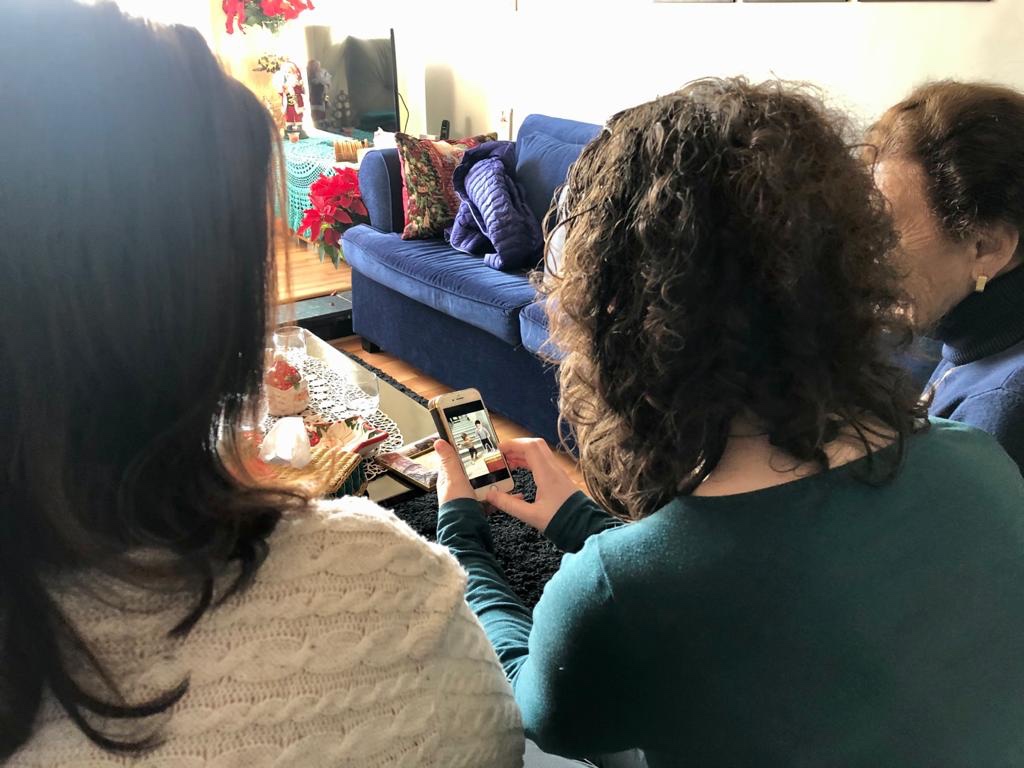

Aristotle observed “the old need friends to care for them and support the actions that fail because of weakness” and friendships aimed at useful results tend “to arise especially among older people, since at that age they pursue the advantageous.” Because of their frailty, older people may depend on others to ensure their physical wellbeing and because of their age, they may be especially concerned about conserving their acquisitions. He says, “Among sour people and older people, friendship is found less often, since they are worse-tempered and find less enjoyment in meeting people, so that they lack the features that seem most typical and most productive of friendship. That is why young people become friends quickly, but older people do not, since they do not become friends with people in whom they find no enjoyment—nor do sour people.”

This is coherent with 89-year-old Douglas Walker’s account of life at a retirement home: “Unlike soldiers, prisoners or students, we at the lodge are here voluntarily and with no objective other than to live. We don’t have a lot in common other than age (and means). However we are encrusted with 70 or 80 years of beliefs, traditions, habits, customs, opinions and prejudices. We are not about to shed any of them, so the concept of community is rather shadowy.”

Continue reading