Today my friend Max told me the story of a turning point in his life.

It was summer vacation and he was a seventeen-year-old teaching English in Spain at a camp for boys.

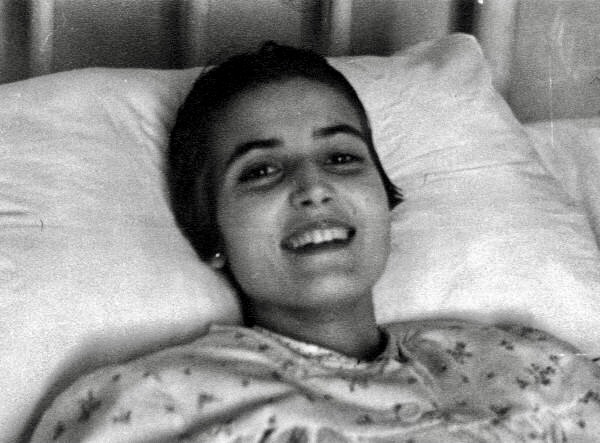

During the camp, he came across this prayer card with a short description of Venerable Montse Grases, a young woman who “knew how to find God in the loving fulfillment of her work and study duties, in the small things of each day.”

Montse had been diagnosed with bone cancer as a teenager and, “throughout her illness, she never lost her infectious cheerfulness or her capacity for friendship.”

Max was totally struck by the fact that Montse died when she was 17 – the same age he was then.

Caregiving as a school in humanity

This evening I read a short book written by my friend and colleague’s grandmother.

In the brief memoir, Walk with Me: growing rich through relationships, author Judy Rae reflects on the experience of caring for her husband Joe while he developed Alzheimer’s.

Presented with honesty and infused with a faith, Rae offers a window into how caregiving can be a school in humanity.

Judy recounts the pain and sorrow of watching her husband lose his memory and she does not skirt the undeniably tragic dimensions of this disease.

“I have been told that when a person is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, he is introduced to a world of loneliness, rejection, terror, confusion, misinformation, and termination. Can this tragedy bring with it any victory into our lives?” she asks.

Rae speaks about how Joe became embarrassed and humiliated by what he could no longer do or remember. Despite the continual accompaniment, affection, and affirmation of his wife, Joe’s feelings of uselessness regularly caused him to get frustrated with himself and even to cry.

Redeeming the time

Sometimes I wonder about how we will look back at this Covid period of our lives.

Will this time be regarded as “lost years” or “missing years”?

Will we be able to recall events clearly or will they be blurred, absent the ordinarily vivid and communal expressions of milestones?

And, will trauma and grief be suppressed by gradual good humour and selective nostalgia?

In The Year of Our Lord 1943, Alan Jacobs writes about the effects of the end of World War II saying, “As war comes to an end, and its exigencies cease, and people return to a freedom absent for so long that its return is discomforting, they think of the apparent lawlessness of Nature and Man alike…”

A few pages later, Jacobs says:

He knew how to suffer

Today is the anniversary of the death of a Polish poet named Cyprian Kamil Norwid.

Unfortunately, Janusz Korczak was right when he said, “The world is deaf to the names of many great Poles.”

I first learned about Norwid through reading texts and addresses by John Paul II since the pope quoted him often. Then, when I moved to Lublin, I found more traces of Norwid – from schools bearing his name, to collections of his works in bookstores, to the statue of him on the university campus.

It was during an address in 2001 that Pope John Paul II told representatives of the Institute of Polish National Patrimony: “I honestly wanted to offer my personal debt of gratitude to the poet, with whose work I have been bound by a deep spiritual kinship since my secondary school years.”

He went on to acknowledge that, “Norwid’s poetry was born from the travail of his difficult life.”

“If we die, we want to die together.”

Today I listened to this podcast episode that one of my best friends recommended in which Rahf Hallaq, a 21-year-old English language and literature student, speaks about the terror of experiencing the Israeli airstrikes in Gaza.

“She’s so articulate in humanizing herself and her community,” my friend told me in offering the recommendation.

When I listened, I was amazed. I think it is the first time that I ever cried while listening to a podcast. In fact, there were a couple occasions that I teared up while listening to Rahf share her story.

Apart from geopolitical calculations and political arguments, Rahf gives us a window into the impact that wider events are having on her own life in a way that is very concrete and personal.

In fact, Rahf’s testimony reminded me of what Eva Hoffman noticed about a Dutch Jewish woman who kept a diary during the Holocaust when she said, “Etty Hillesum lived at a time when the macrocosm of historical events almost completely crushed the microcosm of individual lives.”

Like Etty Hillesum, Rahf Hallaq, through this podcast episode, sought not so much to give a sweeping account of the political situation as to give us an account of her own soul.

It is moving to hear of her speak about her passion for books.

“My dad is the one who made the love of books grow inside me,” she reflects.

Then she shares about the impact of reading Orwell’s 1984 saying, “I mean, when you’re living under oppression, and when you read those books, you feel like you’re not the only one who’s going through this. You feel like these words are actually speaking about you and to you. They give you the power to talk about your own ideas after that.”

Naturally, she was totally devastated about the bombing of a local bookstore that was connected to so many memories for her and her friends.

In the episode, Rahf also speaks about how families in Gaza all huddle together in the same room during the airstrikes because, “If we die, we want to die together.”

Listening to her speak about how her dad used to try to tell her that the bombs were fireworks, in an effort to put her at ease, is also heartbreaking.

My friend was completely right. This story humanized Rahf and the people of Gaza.

It is hard to fathom the real lives of Gazans, but hopefully Rahf will be able to continue bearing witness to “the microcosm of individual lives” by sharing her own experiences with such candor and poise.

What this Holocaust survivor wants on her tombstone

Whenever I read about recently committed antisemitic acts in the news, my heart and mind immediately goes especially to Holocaust survivors. What must it be like to survive the Holocaust and then to be witnessing antisemitism in your own city in the twenty-first century?

Two years ago, after the synagogue shooting near San Diego, I visited my friend Faigie Libman. Faigie is one of two survivors with whom I travelled on a Holocaust study trip to Germany and Poland.

In my clip with her, Faigie says that her motto, which she hopes will go on her tombstone is, “If you have hatred in your heart, there’s no room for love.”

Take a look at this clip. It’s such a good reminder that darkness is best combatted with light and hatred is best combatted with love.

Don’t make yourself afraid

One of the most well-known Hebrew songs, Kol Ha’Olam Kulo has these simple lyrics:

The whole world

is a very narrow bridge

a very narrow bridge

a very narrow bridge

The whole world

is a very narrow bridge –

A very narrow bridge.

And the main thing to recall –

is not to be afraid –

not to be afraid at all.

And the main thing to recall –

is not to be afraid at all.

What does it mean to follow an exemplar?

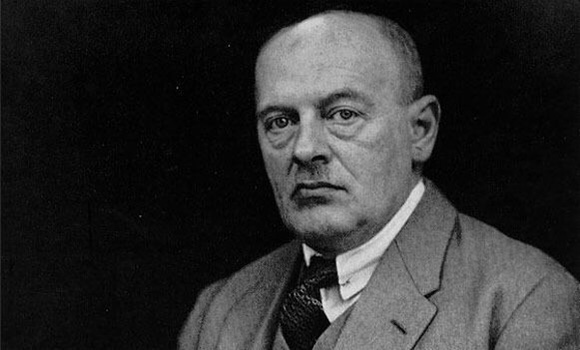

The very interesting philosopher, Max Scheler, died on this date in 1928. He was a prominent influence in ethics, phenomenology, and personalism. He had an eclectic trajectory involving his German Jewish background, his youthful interest in Nietzsche and Marx, his gradual embrace of Catholicism, and his eventual distancing from the Church.

Scheler was quite interesting and imaginative and the impression he made on twentieth century thought is detectable, particularly in many Jewish and Catholic thinkers who address such topics as shame, resentment, and values.

Today I was returning to his book Person and Self-Value and, in particular, to the third section on “Exemplars of Persons and Leaders” in which he reflects on the question of what is actually meant by following an exemplar:

Who exactly am I?

This evening I watched the film “The Father” – a drama that follows an elderly man’s experience of dementia.

The film is masterfully done and its artfulness consists in the way in which the disorientation and confusion of memory loss is simulated for the viewer.

Take a look at the trailer:

This film caused me to wonder: Why do Alzheimer’s and dementia happen specifically? I don’t mean biologically and physiologically, but rather existentially. What does it mean for humans to be the kinds of beings who, at the end of a long, successful, flourishing life can sincerely ask, “Who are you?” and “Who am I?”

Continue readingNationality and Death

A couple years ago, two of my friends who I greatly respect both recommended within a short time span of one another that I read Michael Brendan Dougherty’s book, My Father Left me Ireland.

I happened to read it during the 2019 federal election campaign.

These paragraphs, in particular, really struck me:

We are used to conceiving of the nation almost exclusively as an administrative unit. A nation is measured by its GDP, its merit is discovered in how it lands on international rankings for this or that policy deliverable. A nation may have a language, but the priority is to learn the lingua franca of global business. Our idea of doing something for the nation is reduced to something almost exclusively technical. Policy wonks are the acknowledged legislators of the world.

But there is nothing technical about the Rising. I see in the Rising that a nation cannot live its life as a mere administrative district or as a shopping mall; nations have souls. It’s a virtue when poetry colonizes our politics, even if today the situation is reversed. The life of a nation is never reducible to mere technocracy, just as the home cannot be, no matter how much we try to make it so. I see that nationality is something you do, even with your body, even with your death.

To some, the description of the nation as “an administrative unit” and “technocracy” might sound just right.

But, as is often the case, juxtaposition brings clarity and there is something attractive in the poetry of the irreducible and soulful idea of the nation about which Dougherty speaks.