“I render my thanks and return to my work, to the blank page which every day awaits us poets so that we shall fill it with our blood and our darkness, for with blood and darkness poetry is written, poetry should be written.”

Imagine hearing those words at the conclusion of a brief speech by a laureate of the Nobel Prize in Literature at an extravagant banquet.

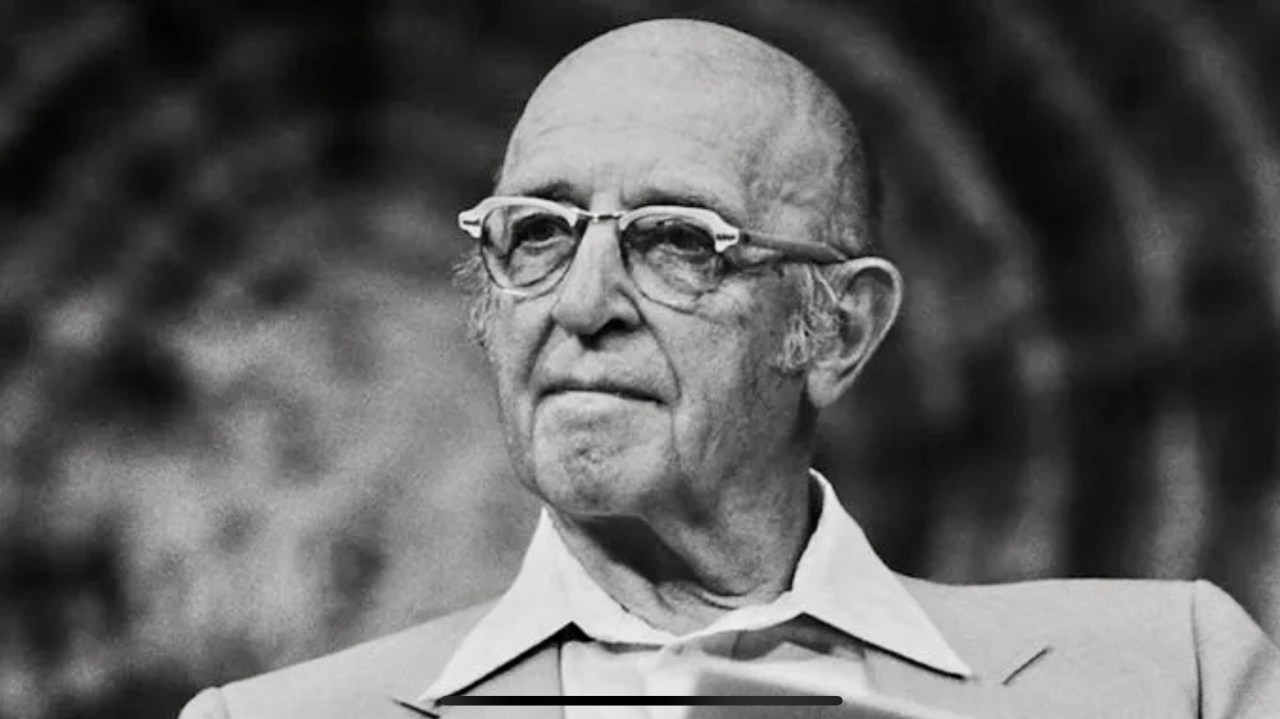

Pablo Neruda, who died on September 23, 1973, was a poet and diplomat from Chile who, in 1971, received this prize.

Here is an excerpt from his acceptance speech:

Dying to Anonymity

I recently started reading Carl Rogers’ very interesting book titled, On Becoming a Person: A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy.

There are many gems already, but check out this one in particular with my emphasis added:

During this past year the Student Union Forum Committee at Wisconsin made a somewhat similar request. They asked me to speak in a personal vein on their “Last Lecture” series, in which it is assumed that, for reasons unspecified, the professor is giving his last lecture and therefore giving quite personally of himself. (It is an intriguing comment on our educational system that it is assumed that only under the most dire circumstances would a professor reveal himself in any personal way.) In this Wisconsin talk I expressed more fully than in the first one the personal learnings or philosophical themes which have come to have meaning for me. In the current chapter I have woven together both of these talks, trying to retain something of the informal character which they had in their initial presentation. The response to each of these talks has made me realize how hungry people are to know something of the person who is speaking to them or teaching them. Consequently I have set this chapter first in the book in the hope that it will convey something of me, and thus give more context and meaning to the chapters which follow.

This excerpt causes me to speculate that, perhaps one reason why people tend to fear both mortality and public speaking so much is the same: it amounts to a death to anonymity. The person is revealed in an eminent way that is vulnerable and transparent. And, interestingly, this can be attractive and hospitable for others who can be received into a story without posturing and pretence, but filled with sincerity and reality.

Two Kinds of Dignity

The philosopher Robert Spaemann has taught me to understand how there are two kinds of dignity. First, there is the universal dignity that all persons have by virtue of being human. This is also discussed within bioethics as fundamental human equality. Secondly, there is dignity that accords with a person’s particular worthiness owing to the virtue of an office, rank, or moral excellence.

Some healthcare professionals purport to have such neutrality and objectivity so to be inclined to treat every person equally according to the first kind of universal dignity characteristic of all human beings.

But persons, being persons, have a natural regard for both kinds of dignity.

Continue readingMore care > Less suffering

This evening I read a chapter from Gilbert Meilaender’s book, Bioethics and the Character of Human Life: Essays and Reflections.

Here is one paragraph that particularly captured my attention:

Continue readingThus, although compassion surely moves us to try to relieve suffering, there are things we ought not to do even for that worthy end–actions that would not honour or respect our shared human condition. One of the terrible truths that governs the shape of our lives is that somethings there is suffering we are unable–within the limits of morality–entirely to relieve. Hence, the maxim that must govern and shape our compassion should be “maximize care,” which may not always be quite the same as “minimize suffering.”

A Lesson in Disinterestedness

Is it really possible to teach lessons about knowledge being for its own sake and learning being its own reward? How, in our hyper-utilitarian age of credentials, competition, and consumerism can such things be instilled and affirmed?

Here is a story from when I studied in Poland.

It so happened that I would be absent on the date of a scheduled exam in “Main Problems in Philosophy” due to a conference and so I arranged to write my exam in the professor’s office in advance.

I showed up to his office at 1 o’clock and he handed me a piece of paper with two questions that he had written out for me:

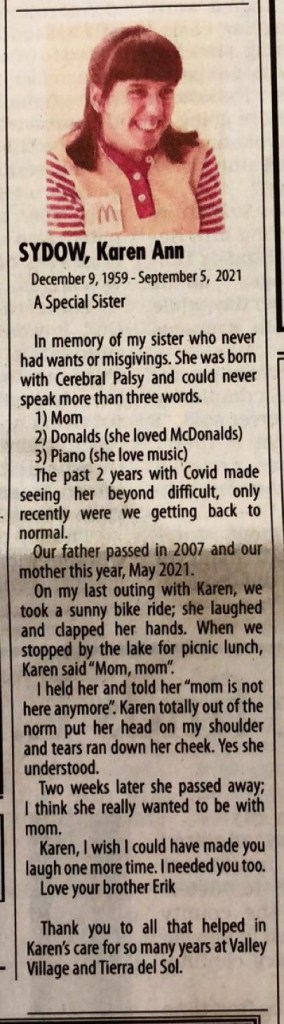

Continue readingWhy millions are paying attention to one obituary

By now dozens of news articles have written about this obituary that has been seen and shared by millions of people around the world.

Cobbled Remembrance

On my walk home from university the other day, I came upon these Stolpersteine – “stumbling stones” – which are brass cubes laid among the cobblestones in remembrance of the Holocaust victims who once lived in various places throughout Europe.

To date more than 75,000 of these mini memorials have been laid throughout the continent.

When I tried to search the names on the stones that I had seen, I found several news articles reporting that these stones had been stolen and then replaced.

“Once a flower, I have become a root.”

I have got to share with you this remarkable excerpt from Pope Francis’s recent address to members of the Jewish community in Hungary:

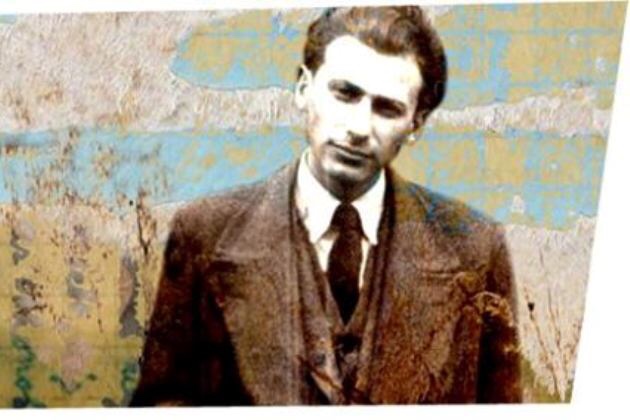

Continue readingI am moved by the thought of all those friends of God who shone his light on the darkness of this world. I think in particular of Miklós Radnóti, a great poet of this country. His brilliant career was cut short by the blind hatred of those who, for no other reason than his Jewish origins, first prevented him from teaching and then separated him from his family.

Imprisoned in a concentration camp, in the darkest and most depraved chapter of human history, Radnóti continued until his death to write poetry. His Bor Notebook was his only collection of poems to survive the Shoah. It testifies to the power of his belief in the warmth of love amid the icy coldness of the camps, illumining the darkness of hatred with the light of faith. The author, crushed by the chains that constrained his soul, discovered a higher freedom and the courage to write that, “as a prisoner… I have taken the measure of all that I had hoped for” (Bor Notebook, Letter to his Wife). He also posed a question that resonates with us today: “And you, how do you live? Does your voice find an echo in this time?” (Bor Notebook, First Eclogue). Our voices, dear brothers and sisters, must not fail to echo that Word given us from Heaven, echoes of hope and peace. Even if no one listens or we are misunderstood, may our actions never deny the Revelation to which we are witnesses.

Finally, in the solitude and desolation of the concentration camp, as he realized his life was fading away, Radnóti wrote: “I am now myself a root… Once a flower, I have become a root” (Bor Notebook, Root). We too are called to become roots. For our part, we usually look for fruits, results or affirmation. Yet God makes his word fruitful on the earth with a soft rain that makes the fields flower (cf. Is 55:10). He reminds us that our faith journeys are but seeds, seeds that then become deep roots nourishing the memory and enabling the future to blossom. This is what the God of our fathers asks of us, because – as another poet wrote – “God waits in other places; he waits beneath everything. Where the roots are. Down below” (Rainer Maria Rilke, Vladimir, the Cloud Painter). We can only reach the heights if we have deep roots. If we are rooted in listening to the Most High and to others, we will help our contemporaries to accept and love one another. Only if we become roots of peace and shoots of unity, will we prove credible in the eyes of the world, which look to us with a yearning that can bring hope to blossom. I thank you and I encourage you to persevere in your journey together, thank you! Please forgive me for speaking while seated, but I am no longer fifteen years old! Thank you.

Death Rehearsal

This year I came upon this interesting sermon for Yom Kippur titled, “Let Death Be Our Teacher.”

This piece explains the way in which Yom Kippur is traditionally understood to be “a rehearsal of our death.”

In it, Rabbi Dara Frimmer says:

Continue readingLet’s be honest, most of us wait until a crisis is upon us to make significant changes in our lives.

My father had a great life before he was diagnosed. He worked hard AND played golf every Wednesday. He loved photography, travel, and good food. He collected recipes from the New York Times and once a month our kitchen would become a gastronomy lab.

And when he was diagnosed, as most of us might do, he took account of his life – a Cheshbon Ha- Nefesh – literally, an accounting of his soul. Which is exactly what we are asked to do on Yom Kippur. A Cheshbon HaNefesh invites us to take inventory: Are we wasting moments of our life or are we lifting up and celebrating what is most precious?

The Triumph of the Cross

The September 14th feast day of the Triumph of the Cross (also known as the Exaltation of the Cross) is a reminder of the paradox that the greatest tragedy became the greatest triumph.

To think that the Nazi propaganda film The Triumph of the Will was released in 1935, four years before a Jewish-Catholic named Edith Stein wrote the following words in addressing her religious community on the September 14th feast…