This evening I’ve been reading Tomáš Halík’s book, I Want You To Be: On the God of Love in which the thirteenth chapter is titled, “Stronger than Death.”

In this chapter, the Czech priest, philosopher, and Templeton Prize laureate discusses how, “in order to perceive death as a gift, one must first deeply experience life as a gift.”

Gratitude is the appropriate response to a gift but, importantly, life is not only a gift but also a responsibility. Halik, like Abraham Joshua Heschel, speaks of life as an assignment:

Death is not a mere returning of the gift of life. Only loans are returned, and to return a gift is always regarded as an insult to the donor. The entrance ticket to life (think of the conversation between Alyosha and Ivan Karamazov) is not returnable. Life is not just a gift; it is also an assignment. At the moment of death, the handing on of the life that was given to us as an opportunity and entrusted to us as a task is—in religion terms—a sort of completed task report, the hour of truth about the extent to which we have fulfilled or squandered the opportunity we were given. Aversion to that religious concept of death is possibly only assisted by arguments from the arsenal of materialistically interpreted science, although in fact it is more likely based on the anxiety aroused by the need to render an account to a Judge who cannot be bribed or influenced. Compared to that the atheist view that everything comes to an end at death is a comforting dose of opium!

How often do we consider giving God an inventory about how we have spent our lifetime?

To be accountable for our days is a basis for man’s proper dignity.

As Antoine de Saint-Exupéry put it, “To be a man is, precisely, to be responsible.”

And responsibility is not only a matter of what we do but, most importantly, of who we become through the moral footprint of our deeds in this world.

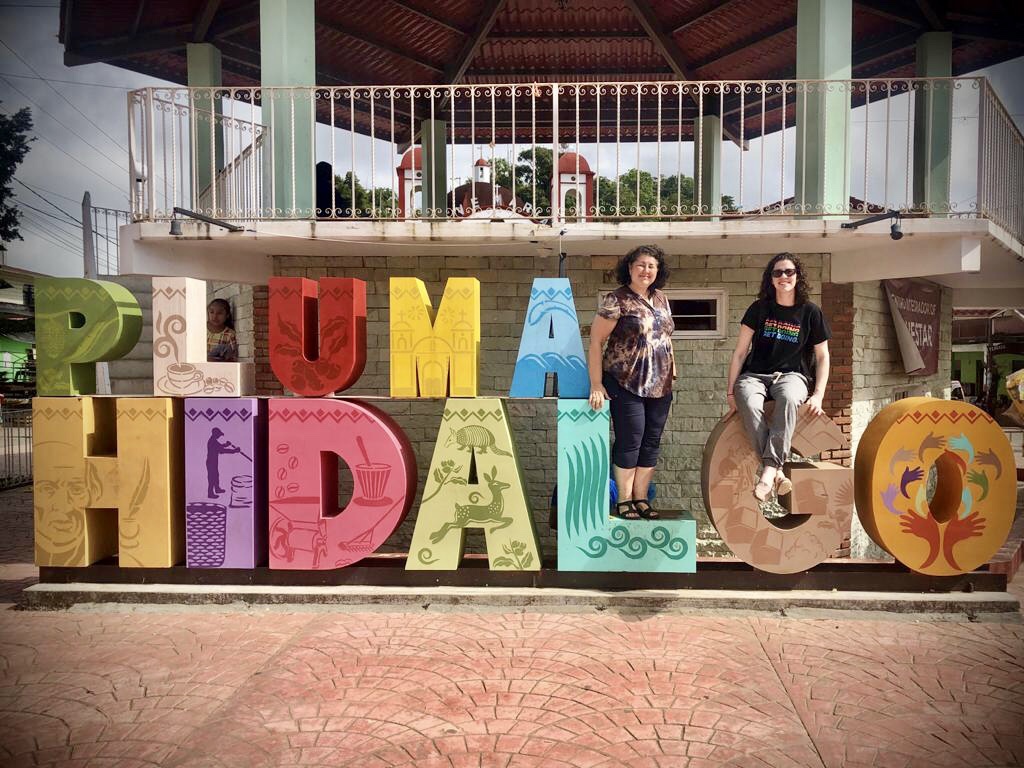

Photo: With Fr. Tomáš Halík in Prague in April 2016