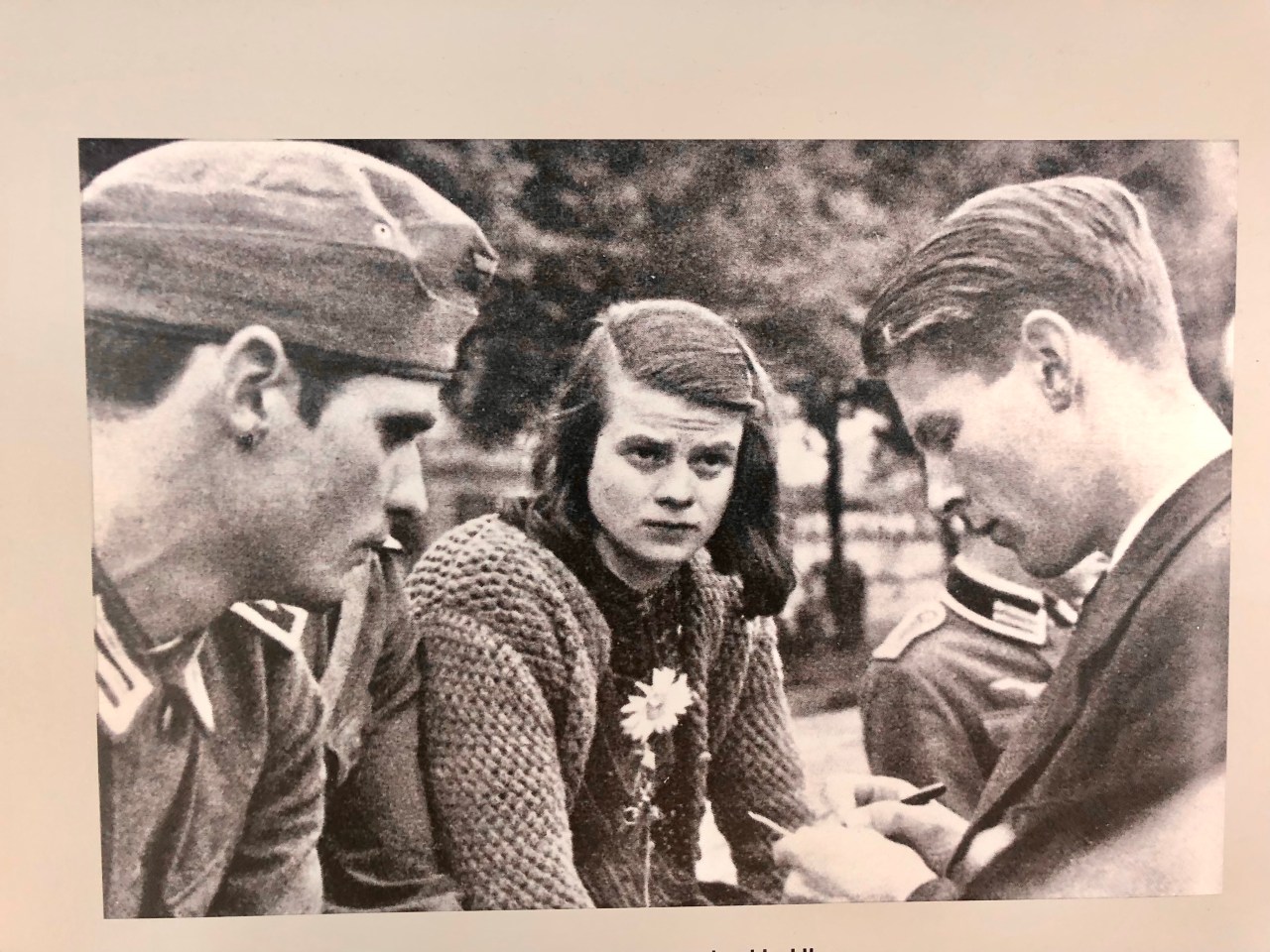

Today is the Feast Day of St. Maximilian Kolbe, the Polish priest who willingly offered to take the place of a prisoner destined for death in Auschwitz.

For many years this story has permeated my moral and spiritual imagination, and it has always been a great honour to get to share this remarkable story for the first time.

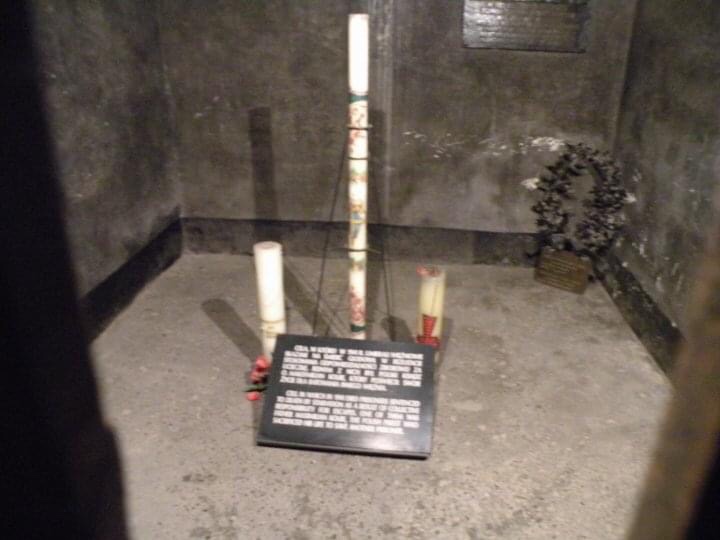

When you visit Auschwitz, it is possible to see the starvation cell in which Maximilian was held and to contemplate this story of sacrifice.

Maximilian’s selfless act was not a moral fluke. It was, to use an expression a friend offered recently, very much “in character.”

Earlier this year I heard another anecdote about Kolbe that I hadn’t heard before. I don’t have the source for it with me now, but from memory I will endeavour to retell it.

It is told that there was a prisoner in Auschwitz who was made to retrieve a corpse from a pile of bodies and move it to another place, probably to be burned. This prisoner, a Catholic man, was so repulsed by the pile of corpses that he could hardly bring himself to do it. Of course, not complying would have its own consequences for him. Fr. Maximilian saw this man’s distress and, looking between this man and then to the pile of bodies, whispered, “And the Word was made flesh.”

At this, a slight brightness returned to the prisoner’s eyes and he was consoled by this word (and the Word) to the extent that he was able to pick up the dead body and carry it reverently.

I am so taken by this story that shows that the Incarnation is a breakthrough. The compassion that God has for man is shown in His willingness to come alongside us and lift us up from the world of sin and darkness.

Will we have the courage, whenever and wherever we see a desecration of persons, to give encouragement and consolation with the poignant reminder that God is truly with us?