The other day, my friend Ada and I were discussing the discovery of Indigenous children’s undocumented remains outside of the former residential school in Kamloops.

Ada is passionate about the Arctic and through her studies, research, and work is involved in cooperating with Inuit in the north with sensitivity, respect, and mutuality.

I could tell the news had shaken her and so I asked whether she had ever been to a First Nations cemetery.

“Yes, twice,” she said.

It was 2018 and Ada had just completed her undergraduate degree at the University of Victoria. As a member of the Catholic Students’ Association, she joined four other students, led by university chaplain, former Anglican-turned-Catholic priest, Fr. Dean Henderson, on a cultural mission exchange to a First Nations reserve in British Columbia.

Think about what freedom really means

This evening I am recalling going with a friend to France on a trip that we themed: “Corpses, Cathedrals, and Combat.”

During our roadtrip through Normandy, we visited Bayeux.

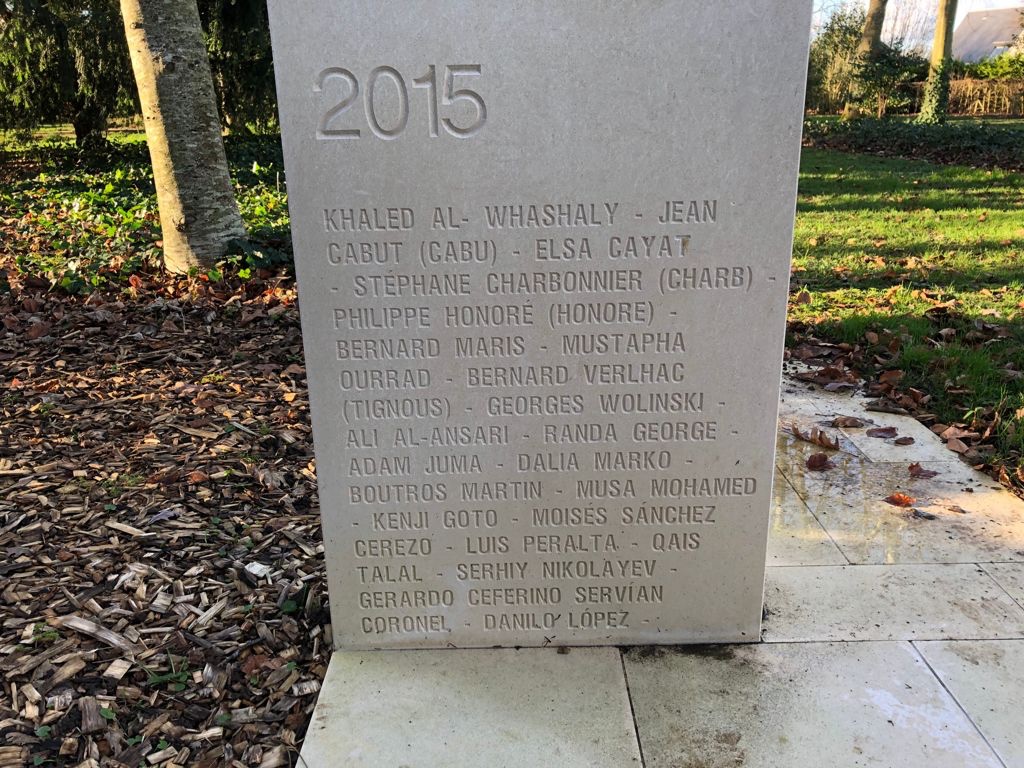

There we came upon a memorial park, at the entrance to which we found a monument that said:

“Bayeux, which has witnessed a freedom dearly won has included the Memorial to Reporters in its ‘Liberty Alley’ to encourage the younger generations to think about what freedom really means.”

Parallel to that is a monument that says “Memorial to Reporters” and then:

“This place is dedicated to reporters and to freedom of the press. It is unique in Europe, forming a walkway among the stones engraved with the names of journalists killed all over the world since 1944.”

I took these monuments in with earnestness and solemnity, and I made a point of stopping especially at the monument that included the names of the Charlie Hebdo satirical journalists killed by Islamists in 2015 since I remembered this so well.

“Every day is a good day to die.”

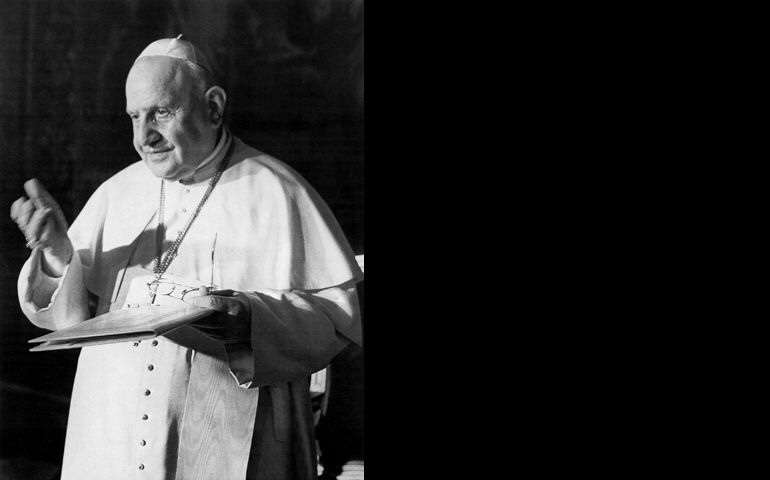

On this anniversary of Saint John XXIII’s death, I took the opportunity to re-read Hannah Arendt’s chapter, “Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli: A Christian on St. Peter’s Chair from 1958 to 1963” in her book Men in Dark Times.

It is an amusing title for the German Jewish political theorists reflections on his pontificate and, more broadly, his whole life and death.

By calling him “A Christian” in this emphatic sense, she intended to convey the remarkable extent to which Pope John XXIII wanted to follow Christ, “to suffer and be despised for Christ and with Christ”, and to “care nothing for the judgments of the world, even the ecclesiastical world.”

The Humanness of Burial

I was pleased to see Fr. Raymond de Souza’s piece in the National Post titled, “What happened at the Kamloops residential school was an offence against humanity.”

In it, he discusses the thought of Hans Jonas, a German Jewish philosopher about whom I wrote my undergraduate thesis.

Separately from that thesis but very much related to these themes, I wrote this short academic paper in 2017 about what it is that sets human persons apart from animals and machines.

Neither apathy nor indifference

“My public life is before you; and I know you will believe me when I say, that when I sit down in solitude to the labours of my profession, the only questions I ask myself are, What is right? What is just? What is for the public good?” – Joseph Howe

It was on this date in 1873 that Joseph Howe, “Defender of Freedom of the Press and Champion of Responsible Government in Nova Scotia” died in Halifax. He was a journalist, editor, newspaper owner, poet, member of parliament, president of the Privy Council, premier, and lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia.

A few years ago, while visiting Halifax, I chose to visit his grave at which I took the opportunity to read aloud with a friend Howe’s 1851 Letter to Electors, which ends with the poetic words: “A noble heart is beating beneath the giant ribs of North America now. See that you do not, by apathy or indifference, depress its healthy pulsations.”

Joseph Howe is known (if he is known at all, and that is rather unlikely in Canada these days) for having been charged with libel against which he argued passionately for “six hours and a quarter.” The charge came after his newspaper, the Novascotian, published a letter criticizing local politicians and exposing their corruption.

To get a taste of his rhetorical style, here is a brief excerpt:

It Is Well With My Soul

Usually people find a powerful association between a certain song and a particular memory, or perhaps even a whole season of their life. But this is a post about how a family came to cherish the association between one song and a person’s entire life – and death.

When Anna was in junior high school, her family befriended a family of Bulgarian immigrants to Canada through their church. The family consisted of parents, Ivan and Rhoda, and their three young children.

Over the years, the two families became quite close.

Anna was in Grade 10 when she and her family found out that both Ivan and Rhoda had received terminal cancer diagnoses.

In order to support the family while still affording them their privacy, Anna’s parents added an extension to their home for them.

There was a time during which Anna remembered Rhoda working so hard to cook healthy concoctions that might enable her to live a bit longer.

Where is Your Devotion to the Mystery of the Person?

Recently, I sat down with my friend Anna to listen to some of her stories.

It might surprise you that this young woman told me, “The happiest time of my life was working 16-hour days in a retirement home during COVID.”

“My body ached and my heart rejoiced,” Anna testified.

She spoke with such empathy about the elderly residents.

“Imagine! A person who has lived a hundred years might be reduced to ‘June at Table 20.’ The residents might have lived a long, fruitful life only to be reduced to their dietary preferences in their final months and years.”

Because Anna regards these seniors’ long lives with reverence, she does not like to see nor participate in taking such a reductive view of the human person.

Instead, she relishes doing her utmost to serve the residents and considers every conversation as an opportunity for a meaningful interaction.

“My favourite residents are the ones who would get agitated easily,” Anna told me. “And it became a challenge: ‘How can I make them happy?'”

The beauty of deeds without repayment

This evening my friend shared a story with me about a couple she knows.

The couple is in their 80s and both the husband and wife are undergoing the loss of their memory.

This couple has been married for more than sixty years and they have three adult children.

One son and one daughter, who each have families of their own, have been committed to caring for their aging parents in the home in which they had all spent their life together as the children were being raised.

In an effort to preserve the routine and normalcy of family life, and in order to avoid needing to put the parents into a long-term care home, the adult son and daughter have developed a ritual of care.

Every single day, for the past six years, the daughter arrives to the home at 11:00 a.m. to serve her parents lunch.

And every single day, for the same six years, the son has arrived at 5:00 p.m. to serve dinner to his parents and then to open the door to the personal support workers who then take over in assisting with the parents’ care into the evening.

Can the old and young be friends?

Here is a short piece I wrote a few ago on the value of and the possibility for intergenerational friendships.

During the Year of the Family, Pope Francis devoted one of his Wednesday addresses to the elderly and another one to grandparents. He thinks that part of the culture of death is a poverty of intergenerational friendships: “How I would like a Church that challenges the throw-away culture with the overflowing joy of a new embrace between young and old!” What are the obstacles to such an embrace? In his Ethics, Aristotle observed that young people tend to seek pleasure in friendships and that the old tend to seek friends for utility, but that good, enduring friendships involve being friends for the other’s own sake. Given the distinct tendencies to which the old and young are prone, can they actually be friends?

Aristotle observed “the old need friends to care for them and support the actions that fail because of weakness” and friendships aimed at useful results tend “to arise especially among older people, since at that age they pursue the advantageous.” Because of their frailty, older people may depend on others to ensure their physical wellbeing and because of their age, they may be especially concerned about conserving their acquisitions. He says, “Among sour people and older people, friendship is found less often, since they are worse-tempered and find less enjoyment in meeting people, so that they lack the features that seem most typical and most productive of friendship. That is why young people become friends quickly, but older people do not, since they do not become friends with people in whom they find no enjoyment—nor do sour people.”

This is coherent with 89-year-old Douglas Walker’s account of life at a retirement home: “Unlike soldiers, prisoners or students, we at the lodge are here voluntarily and with no objective other than to live. We don’t have a lot in common other than age (and means). However we are encrusted with 70 or 80 years of beliefs, traditions, habits, customs, opinions and prejudices. We are not about to shed any of them, so the concept of community is rather shadowy.”

Continue reading“All My Friends Are Dead.”

Never underestimate how much it can delight an author to hear from an appreciative reader.

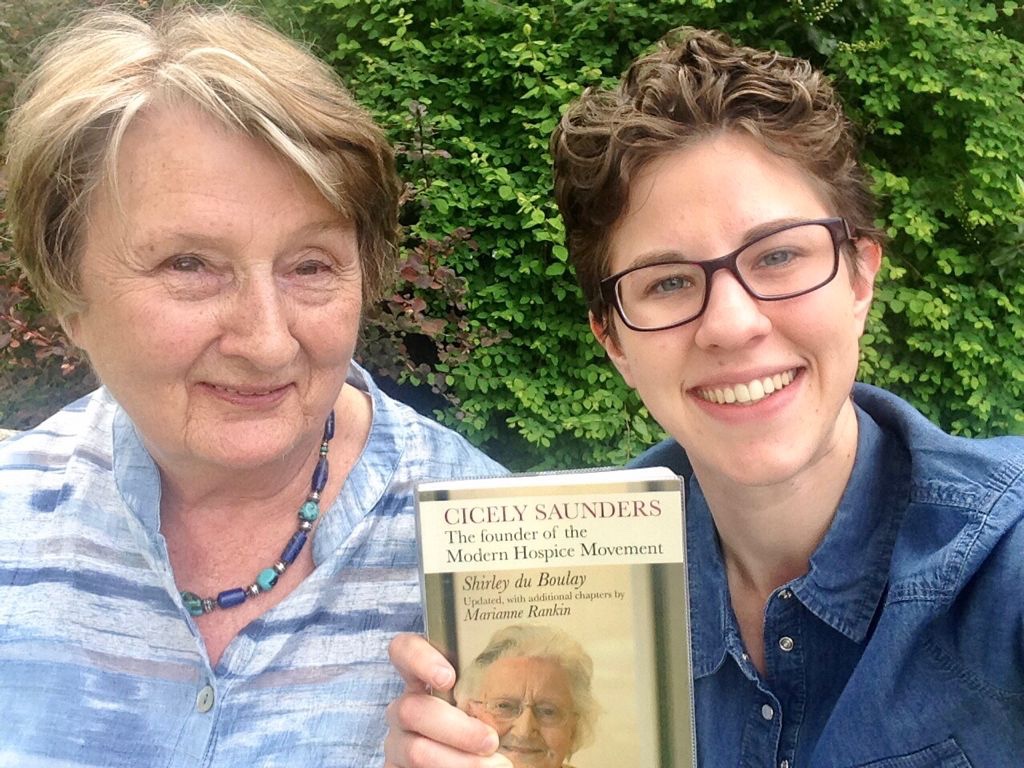

On this date five years ago, I had the opportunity to meet the author of a book I really enjoyed.

It was the day after I had attended the 2016 Templeton Prize Ceremony honouring Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks when I set off to Oxford to meet the author of a biography of another Templeton Prize winner, Cecily Saunders.

Saunders’ biographer Shirley du Boulay was in her early 80s. She had received my handwritten letter of approximately eight pages praising her for her beautiful biography of the founder of the modern hospice and palliative care movement in the U.K. and eventually sent me an email in reply.

Naturally, I was thrilled when she invited me to her Oxford home for tea should I ever be passing through.

I took a cab from the Oxford bus station to her address and arrived just before 1 o’clock.

I rang the bell and, a moment later, she answered.

As I followed her inside, she hurriedly began to prepare a light lunch even though I’d insisted on only coming for tea.

The table was set in a lovely manner and there was a bottle of rosé, meats, potato salad, green salad, bread, and butter.