This evening I finished reading Jordan Peterson’s latest book, Beyond Order: 12 More Rules for Life.

In the last chapter, Rule XII: Be grateful in spite of your suffering, Peterson mentions that he has repeatedly suggested to his various audiences “that strength at the funeral of someone dear and close is a worthy goal” and he notes that “people have indicated to me that they took heart in desperate times as a consequence.”

After a worldwide book tour and many other public appearances, Peterson has had the opportunity to test and play with his ideas with many audiences. And it is interesting to read his thoughtful reflections based on his careful observation of the reactions of persons in the audience.

Earlier in the book, he mentions, as he has said elsewhere, that he sees people’s faces light up whenever he speaks about responsibility. Peterson is keenly aware that people have been raised with a greater emphasis on rights and the corresponding sense of entitlement that ensues with this focus. Yet, a sense of responsibility is what ennobles and fills persons with a sense of their proper dignity and capacity.

Accordingly, this challenge to have strength at funerals is an extension of his usual exhortation to responsibility.

He writes:

Responsibility

“Our lives no longer belong to us alone.”

It was on this date five years ago that Elie Wiesel died.

The Holocaust survivor and Nobel laureate felt a tremendous responsibility to bear witness to all that he and others suffered.

“If I survived, it must be for some reason: I must do something with my life. It is too serious to play games with anymore because in my place someone else could have been saved. And so I speak for that person. On the other hand, I know I cannot,” he told a New York Times interviewer in 1981.

This evening I re-read Wiesel’s brief Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech from a few years later in 1986.

Don’t Die Twice

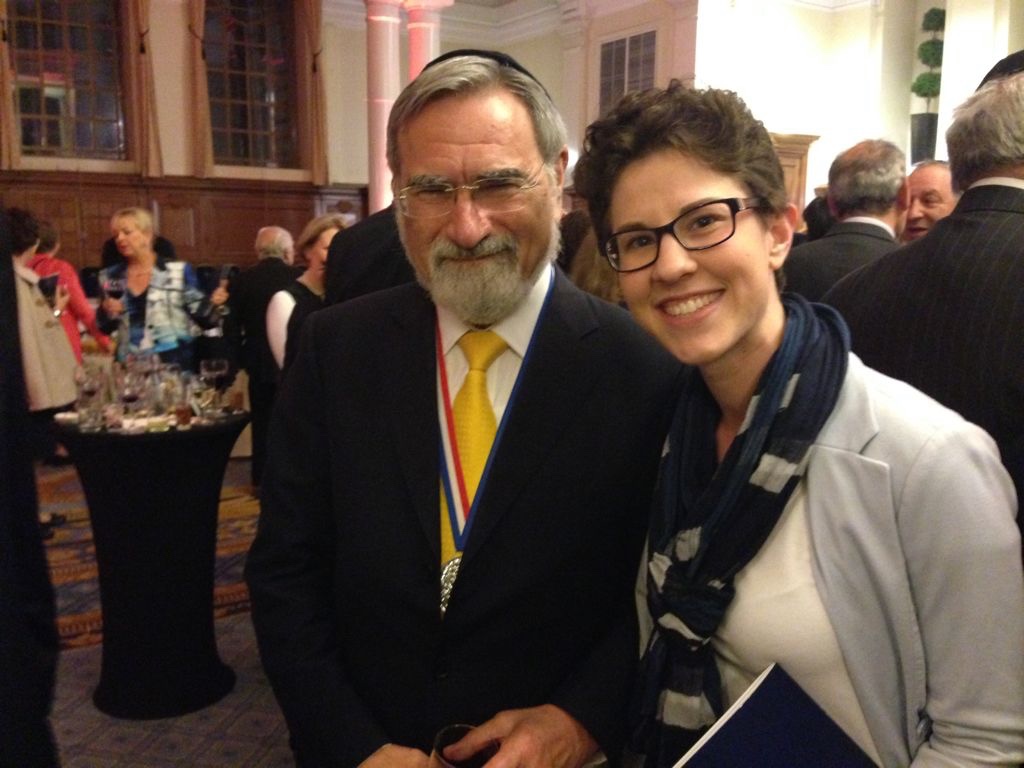

Recently I have been reflecting on a particular chapter in the last book Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks published just before his death. The book is titled Morality: Restoring the Common Good in Divided Times and the chapter that I have in mind is titled “Victimhood.”

Rabbi Sacks opens the chapter with a discussion of Yisrael Kristal, a Holocaust survivor who lived to be 113.

During the Holocaust, Yisrael’s wife and children were murdered. And, after years in ghettos and concentration camps, he weighed just 82 pounds.

We learn that Yisrael remained a religious Jew throughout his life. He married another survivor with whom he had children and they settled in Haifa and opened a business selling sweets and chocolates as he had done in Poland.

Rabbi Sacks goes on to compare Yisrael Kristal to Abraham insofar as Yisrael was able to integrate into his life completely the transformative idea: “To survive tragedy and a trauma, first build the future. Only then, remember the past.”

“There are real victims,” Rabbi Sacks affirms. “And they deserve our empathy, sympathy, and compassion. But there is a difference between being a victim and defining yourself as one. The first is about what happened to you. The second is about how you define who and what you are. The most powerful lesson I learned from these people I have come to know, people who are victims by any measure, is that, with colossal willpower, they refused to define themselves as such.”

This Is What Indigenous-Catholic Reconciliation Looks Like

The other day, my friend Ada and I were discussing the discovery of Indigenous children’s undocumented remains outside of the former residential school in Kamloops.

Ada is passionate about the Arctic and through her studies, research, and work is involved in cooperating with Inuit in the north with sensitivity, respect, and mutuality.

I could tell the news had shaken her and so I asked whether she had ever been to a First Nations cemetery.

“Yes, twice,” she said.

It was 2018 and Ada had just completed her undergraduate degree at the University of Victoria. As a member of the Catholic Students’ Association, she joined four other students, led by university chaplain, former Anglican-turned-Catholic priest, Fr. Dean Henderson, on a cultural mission exchange to a First Nations reserve in British Columbia.

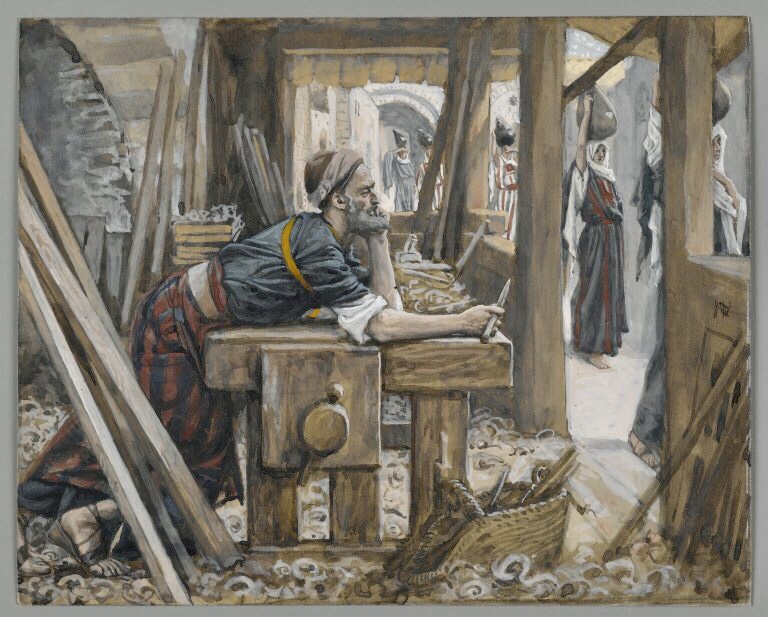

Is your work to die for?

Today is the feast of St. Joseph the Worker and this post examines Pope Francis’ beautiful Apostolic Letter “With A Father’s Heart” to explore the practical ways in which we can see work as a context for self-gift through which we fulfill the meaning of our lives.

I have organized the themes of the letter into the following eight categories. Each category begins with a excerpt from the letter and then includes a question or two for our contemplation of some possible practical applications.

1. Names and Relationships:

What would you do with a longer life, anyway?

I just finished re-reading Leon Kass’s splendid essay, “L’Chaim and Its Limits: Why Not Immortality?“

I was reminded of that 2001 piece when I read this interview published yesterday about Archbishop Emeritus Charles Chaput’s new book Things Worth Dying For: Thoughts on a Life Worth Living.

Leon Kass begins his piece by exploring the primacy of life in Judaism and our wider culture’s interest in prolonging life and forestalling death.

Then, he raises some questions:

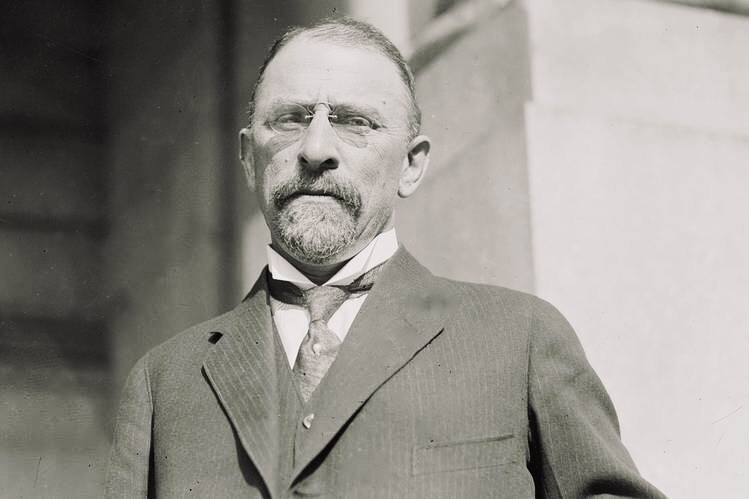

When genocide concerns you

Today is Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day and I’ve been reading through Ambassador Morgenthau’s Story: A Personal Account of the Armenian Genocide while eating some Armenian snacks from my Ararat Box.

Genocide is a weighty word and the recognition of it implies our moral responsibility not to be bystanders to the egregious evils of which we admit being aware.

During the First World War, Henry Morgenthau, a German-born Jewish American was serving as the the fourth 4th US Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire.

As ambassador, he did his utmost to try to reason with the Ottoman authorities, to stop the genocide, and to implore the U.S. government on behalf of the Armenians, Greeks, and Assyrians who were being persecuted and massacred.

The Task Report in Death

This evening I’ve been reading Tomáš Halík’s book, I Want You To Be: On the God of Love in which the thirteenth chapter is titled, “Stronger than Death.”

In this chapter, the Czech priest, philosopher, and Templeton Prize laureate discusses how, “in order to perceive death as a gift, one must first deeply experience life as a gift.”

Gratitude is the appropriate response to a gift but, importantly, life is not only a gift but also a responsibility. Halik, like Abraham Joshua Heschel, speaks of life as an assignment:

Death is not a mere returning of the gift of life. Only loans are returned, and to return a gift is always regarded as an insult to the donor. The entrance ticket to life (think of the conversation between Alyosha and Ivan Karamazov) is not returnable. Life is not just a gift; it is also an assignment. At the moment of death, the handing on of the life that was given to us as an opportunity and entrusted to us as a task is—in religion terms—a sort of completed task report, the hour of truth about the extent to which we have fulfilled or squandered the opportunity we were given. Aversion to that religious concept of death is possibly only assisted by arguments from the arsenal of materialistically interpreted science, although in fact it is more likely based on the anxiety aroused by the need to render an account to a Judge who cannot be bribed or influenced. Compared to that the atheist view that everything comes to an end at death is a comforting dose of opium!

How often do we consider giving God an inventory about how we have spent our lifetime?

To be accountable for our days is a basis for man’s proper dignity.

As Antoine de Saint-Exupéry put it, “To be a man is, precisely, to be responsible.”

And responsibility is not only a matter of what we do but, most importantly, of who we become through the moral footprint of our deeds in this world.

Photo: With Fr. Tomáš Halík in Prague in April 2016

“We Gradually Deserve Those Who Demand to Be Helped”

There is a little book by Antoine De Saint-Exupéry called Letter to a Hostage. In the first part, the author paints a scene of emigrants aboard a ship. Even without more context than this, this passage is remarkable:

How to construct a new self. How to remake the heavy skein of memories? That phantom ship was crowded, like Limbo, with souls unborn. The only ones who showed any semblance of reality, so much so that one would have wanted to touch them, were those who, belonging to the ship and ennobled by real duties, carried the trays, polished the brass and shoes and, slightly scornful, served the dead. That slight disregard of the staff towards the emigrants was not due to their poverty. They were not lacking in money, but destiny. They were not attached to any home, to any friend, to any responsibility. They played a part, but it was no longer true. No one wanted them, no one would call on them. What a thrill it is to receive a telegram in the middle of the night, summoning you to the station: “Hurry, I need you!” We soon discover friends to help us. We gradually deserve those who demand to be helped. Of course no one hated my ghosts, no one envied them, no one bothered them. But no one loved them with the only love that is worthwhile. I thought: as soon as they arrive they will be taken into welcome cocktail parties, consolation suppers. But who will ever knock at their doors, begging to be let in. “Open, it’s me!” A child must be fed for a long time before he can demand. A friend must be cultivated for a long time before he claims his due friendship. It is necessary to spend fortunes for generations on repairing an old ruined castle before one learns to love it.

Such realities are best explained through stories and scenes and anecdotes; they are not abstract principles, though they are tinged with the mystery and depth that prevents them from being grasped, especially all at once.

Indeed there are many emigrants passing through life like souls unborn without ties and without purpose. And among the dead of expressive individualists, what could possibly be the meaning of: “We gradually deserve those who demand to be helped”?

Yet, as usual, the clarity comes in the juxtaposition between the cocktail party versus the “Hurry, I need you!”

The human person, every human person, is ennobled by real duties and real attachments. The love that is worthwhile is not “Can I get a photo with you?” or “Here’s my card.” The love that is worthwhile is the demand of someone in need who says and who means, to someone in particular, “It’s me. I need you!”

Treasuring Time

Yes, even on my birthday I keep my death before me. It makes life sweeter by increasing my sense of its preciousness.

A friend of mine gave me a birthday card with this quotation by Josemaria Escriva: “Time is our treasure, the ‘money’ with which to buy eternity.”

On my birthday, I am filled with gratitude and responsibility – gratitude for God’s generosity in giving me these years and responsibility to live and love well with vision, depth, and hope.

I am thankful to my friends and family who have helped me to treasure time in this season – to sincerely savour and cherish it rather than wasting time or wishing it were some other time.

There is no better time, and “my times are in [His] hands.” (Ps. 31:15)